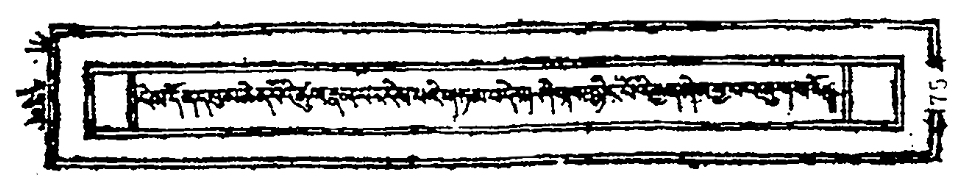

Nges don dbu ma chen po'i tshul rnam par nges pa'i gtam bde gshegs snying po'i rgyan

In this work on Great Madhyamaka, the Ornament of Sugatagarbha, Getse Mahāpaṇḍita discusses the different tenet systems and their brief history and aligns them to the three Turnings of the Wheel of Dharma. He delves into discussion of Madhyamaka and includes both traditions from Nāgārjuna and Asaṅga was Middle Way. He introduces the term coarse outer Middle Way (རགས་པ་ཕྱིའི་དབུ་མ་) to refer to the Mādhyamika tradition which focusses on emptiness as taught in the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras and the subtle inner Middle Way (ཕྲ་བ་ནང་གི་དབུ་མ་) to refer to the teachings on buddha-nature in the last Turning. Getse Mahāpaṇḍita underscores how buddha nature, the innate nature of the mind, or the self cognising awareness is the ultimate reality. He highlights the Great Madhyamaka of other-emptiness as the ultimate truth and identifies that with the final message of the Kālacakra, Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen teachings as well as the final intent of the great masters.