|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| {{Book | | {{Book |

| |BookParentPage=Research/Secondary Sources

| |

| |BookPerson={{Book-person | | |BookPerson={{Book-person |

| | |PersonPage=Wangchuk, Tsering |

| |PersonName=Tsering Wangchuk | | |PersonName=Tsering Wangchuk |

| |PersonPage=Wangchuk, Tsering

| |

| |PersonImage=http://commons.tsadra.org/images-commons/f/f5/Wangchuk_tsering_U_San_Francisco.jpg

| |

| }} | | }} |

| |FullTextRead=No | | |FullTextRead=No |

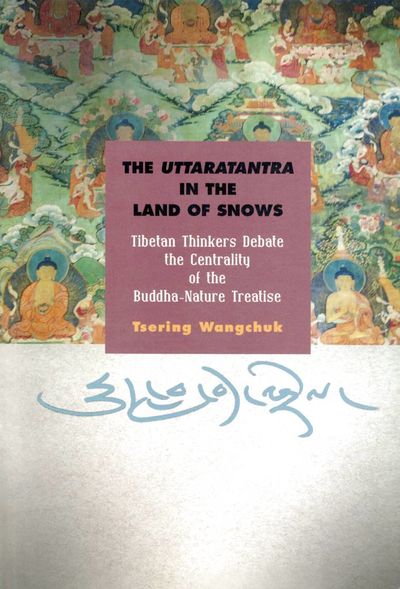

| |BookEssay=Tsering Wangchuk's ''The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows'' is a clear and concise introduction to the history of the Uttaratantra and buddha-nature theory in pre-modern Tibet. It is an ideal introduction for anyone not yet familiar with the buddha-nature debate in Tibet. Wangchuk summarizes the writings and views of several of the most important Tibetan philosophers who weighed in on buddha-nature between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries from Ngok Lotsāwa through Sakya Paṇḍita to Dolpopa and Gyaltsap Je. | | |BookEssay=Tsering Wangchuk's ''The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows'' is a clear and concise introduction to the history of the Uttaratantra and buddha-nature theory in pre-modern Tibet. It is an ideal introduction for anyone not yet familiar with the buddha-nature debate in Tibet. Wangchuk summarizes the writings and views of several of the most important Tibetan philosophers who weighed in on buddha-nature between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries from Ngok Lotsāwa through Sakya Paṇḍita to Dolpopa and Gyaltsap Je. |

|

| |

|

| The book is divided into three main sections: early Kadam thinkers who attempted to fold the Uttaratantra's positive-language teaching on buddha-nature into mainstream Madhyamaka doctrine of non-affirming negation. They did so by asserting that buddha-nature was, in fact, a synonym of emptiness, and was, therefore, a definitive teaching. The second stage was reactions during the thirteenth century. Sakya Paṇḍita, for example, rejected the conflation of buddha-nature and emptiness and declared the teaching to be provisional; early Kagyu thinkers revived the positive-language teachings and asserted that such statements were definitive, and Dolpopa taught "other-emptiness," the strongest expression of positive-language doctrine ever advocated in Tibet. Finally, in the fourteenth century, a number of mainly Geluk thinkers, such as Gyaltsap Je, reacted against Dolpopa and all synthesis of Yogacāra and Madhyamaka thought, relegating the Uttaratantra again to provisional status. | | The book is divided into three main sections: early Kadam thinkers who attempted to fold the Uttaratantra's positive-language teaching on buddha-nature into mainstream Madhyamaka doctrine of non-affirming negation. They did so by asserting that buddha-nature was, in fact, a synonym of emptiness, and was, therefore, a definitive teaching. The second stage was reactions during the thirteenth century. Sakya Paṇḍita, for example, rejected the conflation of buddha-nature and emptiness and declared the teaching to be provisional; early Kagyu thinkers revived the positive-language teachings and asserted that such statements were definitive, and Dolpopa taught "other-emptiness," the strongest expression of positive-language doctrine ever advocated in Tibet. Finally, in the fourteenth century, a number of mainly Geluk thinkers, such as Gyaltsap Je, reacted against Dolpopa and all synthesis of Yogācāra and Madhyamaka thought, relegating the Uttaratantra again to provisional status. |

|

| |

|

| The advantage of Wangchuk's historical frame is that all assertions are placed in the easy context of an opponent or supporter's writing, thus reminding the reader that buddha-nature theory in Tibet is an ongoing conversation, a debate between the two fundamental doctrinal poles of positive and negative descriptions of the ultimate. | | The advantage of Wangchuk's historical frame is that all assertions are placed in the easy context of an opponent or supporter's writing, thus reminding the reader that buddha-nature theory in Tibet is an ongoing conversation, a debate between the two fundamental doctrinal poles of positive and negative descriptions of the ultimate. |

| Line 75: |

Line 73: |

| |PublisherLogo=File:SUNY Press logo.jpg | | |PublisherLogo=File:SUNY Press logo.jpg |

| |PostStatus=Needs Final Review | | |PostStatus=Needs Final Review |

| | |BookParentPage=Research/Secondary Sources |

| }} | | }} |