|

|

| (16 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| {{Book | | {{Book |

| |BookParentPage=Research/Secondary Sources

| |

| |BookPerson={{Book-person | | |BookPerson={{Book-person |

| | |PersonPage=Wangchuk, Tsering |

| |PersonName=Tsering Wangchuk | | |PersonName=Tsering Wangchuk |

| |PersonPage=Wangchuk, Tsering

| |

| |PersonImage=https://commons.tsadra.org/images-commons/f/f5/Wangchuk_tsering_U_San_Francisco.jpg

| |

| }} | | }} |

| |FullTextRead=No | | |FullTextRead=No |

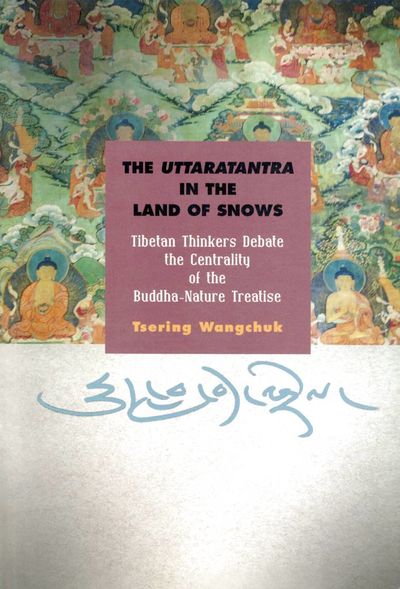

| |BookEssay=Tsering Wangchuk's The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows is a clear and concise introduction to the history of the Uttaratantra and buddha-nature theory in pre-modern Tibet. It is an ideal introduction for anyone not yet familiar with the buddha-nature debate in Tibet. Wangchuk summarizes the writings and views of several of the most important Tibetan philosophers who weighed in on buddha-nature between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries from Ngok Lotsāwa through Sakya Paṇḍita to Dolpopa and Gyeltsabje. | | |BookEssay=Tsering Wangchuk's ''The Uttaratantra in the Land of Snows'' is a clear and concise introduction to the history of the Uttaratantra and buddha-nature theory in pre-modern Tibet. It is an ideal introduction for anyone not yet familiar with the buddha-nature debate in Tibet. Wangchuk summarizes the writings and views of several of the most important Tibetan philosophers who weighed in on buddha-nature between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries from Ngok Lotsāwa through Sakya Paṇḍita to Dolpopa and Gyaltsap Je. |

|

| |

|

| The book is divided into three main sections: early Kadam thinkers who attempted to fold the Uttaratantra's positive-language teaching on buddha-nature into mainstream Madhyamaka doctrine of non-affirming negation. They did so by asserting that buddha-nature was in fact a synonym of emptiness, and was therefore a definitive teaching. The second stage was reactions during the thirteenth century. Sakya Paṇḍita, for example, rejected the conflation of buddha-nature and emptiness and declared the teaching to be provisional; early Kagyu thinkers revived the positive-language teachings and asserted that such statements were definitive; and Dolpopa taught "other-emptiness," the strongest expression of positive-language doctrine ever advocated in Tibet. Finally, in the fourteenth century a number of mainly Geluk thinkers such as Gyeltsabje reacted against Dolpopa and all synthesis of Yogacāra and Madhyamaka thought, relegating the Uttaratantra again to provisional status. | | The book is divided into three main sections: early Kadam thinkers who attempted to fold the Uttaratantra's positive-language teaching on buddha-nature into mainstream Madhyamaka doctrine of non-affirming negation. They did so by asserting that buddha-nature was, in fact, a synonym of emptiness, and was, therefore, a definitive teaching. The second stage was reactions during the thirteenth century. Sakya Paṇḍita, for example, rejected the conflation of buddha-nature and emptiness and declared the teaching to be provisional; early Kagyu thinkers revived the positive-language teachings and asserted that such statements were definitive, and Dolpopa taught "other-emptiness," the strongest expression of positive-language doctrine ever advocated in Tibet. Finally, in the fourteenth century, a number of mainly Geluk thinkers, such as Gyaltsap Je, reacted against Dolpopa and all synthesis of Yogācāra and Madhyamaka thought, relegating the Uttaratantra again to provisional status. |

|

| |

|

| The advantage of Wangchuk's historical frame is that all assertions are placed in easy context of an opponent or supporter's writing, thus reminding the reader that buddha-nature theory in Tibet is an ongoing conversation, a debate between the two fundamental doctrinal poles of positive and negative descriptions of the ultimate. | | The advantage of Wangchuk's historical frame is that all assertions are placed in the easy context of an opponent or supporter's writing, thus reminding the reader that buddha-nature theory in Tibet is an ongoing conversation, a debate between the two fundamental doctrinal poles of positive and negative descriptions of the ultimate. |

| | |BookToc=*{{i|Acknowledgments|xi}} |

| | *{{i|Introduction|1}} |

| | **{{i|General Remarks|1}} |

| | **{{i|Textual Historical Background|5}} |

| | |

| | *{{i|Part I. Early Period: Kadam Thinkers Rescue the Treatise|13}} |

| | **{{i|Chapter 1. Rise of the Uttaratantra in Tibet: Early Kadam Scholars<br>Revitalize the Newly Discovered Indian Exegesis|13}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction|13}} |

| | ***{{i|Ngok and Chapa on the Pervasive Nature of the Buddha-Body|15}} |

| | ***{{i|Ngok and Chapa on Definitive or Provisional Nature in the<br>Uttaratantra |18}} |

| | ***{{i|Ngok and Chapa on the Uttaratantra as a Last Wheel Treatise |19}} |

| | ***{{i|Buddha-Element as a Conceived Object|20}} |

| | ***{{i|Ngok and Chapa Differ on Emphasis|21}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|24}} |

| | **{{i|2. Sowing Seeds for Future Debate: Dissenters and Adherents|25}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction |25}} |

| | ***{{i|Sapen, the Dissenter |26}} |

| | ***{{i|Rikrel, the Third Karmapa, and Sangpu Lodrö Defend the<br>Uttaratantra |29}} |

| | ***{{i|Rinchen Yeshé’s Proto Other-Emptiness Presentation of the<br>Uttaratantra, and Butön’s Reply|34}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|38}} |

| | *{{i|Part II. The Pinnacle Period: the Other-Emptiness Interpretation Spreads |43}} |

| | **{{i|3. Other-Emptiness Tradition: The Uttaratantra in Dölpopa’s Works|43}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction|43}} |

| | ***{{i|Predominance of the Last Wheel Scriptures|44}} |

| | ***{{i|Is the Uttaratantra a Cittamātra Text or a Madhyamaka Text?|46}} |

| | ***{{i|Classification of Cittamātra|48}} |

| | ***{{i|Classification of Madhyamaka|51}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|54}} |

| | **{{i|4. The Uttaratantra in Fourteenth-Century Tibet|55}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction |55}} |

| | ***{{i|Sazang Follows in His Master’s Footsteps|55}} |

| | ***{{i|Two Fourteenth-Century Kadam Masters’ Uttaratantra<br>Commentaries |59}} |

| | ***{{i|Longchenpa’s View on the Uttaratantra|63}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|65}} |

| | *{{i|Part III. The Argumentation Period: Self-Emptiness Proponents criticize<br> Other-Emptiness Approach |69}} |

| | **{{i|5. Challenges to the Purely Definitive Nature of the Uttaratantra: Zhalu<br>Thinkers Criticize Dölpopa |69}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction|69}} |

| | ***{{i|Butön’s Ornament |70}} |

| | ***{{i|Dratsépa’s Commentary|72}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|80}} |

| | **{{i|6. Challenges to the Supremacy of the Uttaratantra: Rendawa and<br>Tsongkhapa on Tathāgata-essence Literature |83}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction|83}} |

| | ***{{i|Rendawa on the Uttaratantra and the Tathāgata-Essence Literature|83}} |

| | ***{{i|Tsongkhapa on the Uttaratantra and the Tathāgata-Essence Literature|89}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|95}} |

| | **7. {{i|Gyeltsap’s Commentary on the Uttaratantra: A Critique of Dölpopa’s Interpretation of Tathāgata-essence Literature|97}} |

| | ***{{i|Introduction|97}} |

| | ***{{i|Middle Wheel and Last Wheel Teachings|101}} |

| | ***{{i|Definitive Meaning and Provisional Meaning|103}} |

| | ***{{i|Self-Emptiness and Other-Emptiness|104}} |

| | ***{{i|Conclusion|106}} |

| | *{{i|Conclusion|109}} |

| | *{{i|General Remarks|109}} |

| | *{{i|Completing the Cycle|112}} |

| | *{{i|Notes|119}} |

| | *{{i|Bibliography|181}} |

| | *{{i|Tibetan Language Works Cited|181}} |

| | *{{i|English Language Works Cited|186}} |

| | *{{i|Index|191}} |

| | |QuotesTabContent={{GetBookQuotes}} |

| | |PublisherLogo=File:SUNY Press logo.jpg |

| | |StopPersonRedirects=No |

| |AddRelatedTab=No | | |AddRelatedTab=No |

| |QuotesTabContent={{GetBookQuotes}} | | |BookParentPage=Research/Secondary Sources |

| |PostStatus=Needs Copy Editing

| |

| }} | | }} |